When learning the Novel, you learn that the first novel emerged in the late 17th century. Such novels recorded voyages to strange new lands and even stranger bodies who peopled the land. On their return, there grew a complete market to consume the literature that was the spectacle of difference. With the innovation of photographs at the turn of the century, every voyage was reserved with at least two weapons: the pen and the camera.

Cara Romero reveals the language of capture, however artistic, is unforgiveable. And yet, remains to be the canon of this art, the photographing eye. As a beginning photographer in a tribal college, Romero emulated what is “out there” and available as the image of First Nations. Outsiders seeking to document “the vanishing race” photographed Native people dressed in regalia and, at times, staged the scene. Romero’s first reproductions of this practice, she sensed, disconnected Native life and Nativehood from the present. “To become a Native American photographer, there was not very much reference for what that meant.” The intensity of this confrontation braves the question of utility. To what extent and to whose advantage can photography really be repurposed? How are the very technologies with a history of harm, at all, useful to the injured? How can someone stolen steal themselves back?

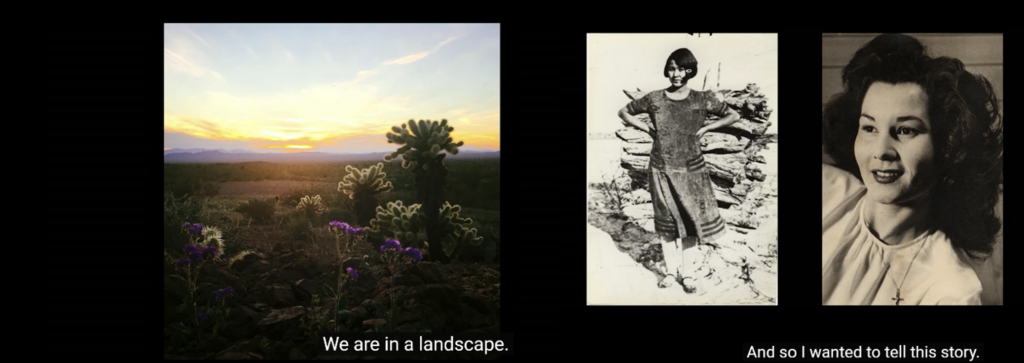

We are as indigenous as we ever were. Romero elevates storytelling as our strongest weapon and answer to that harm. Telling stories is a cultural, anticolonial, ontological, and ecological power that is life-giving, in contrast with ethnographic documentation that hungers to collect the world, as if it ever could. Storytelling is a source for life because it carries memory while memory carries the rest: the people, the land, the water, the culture, the knowledge, the sounds, the senses, the foods, the traditions, the triumphs, the losses, and the ancestors. And without stories, Romero cautions, we have a greater misunderstanding.

The semiotics of indigenous response to the environment can be felt and understood through the land. It is a place to be in/side of, rooted in a distinctive way of being-in-the-world, unlike the viewer or onlooker who sees themselves outside of its geography. Romero’s statement “Standing Rock is everywhere” implies not only a haunting collectivity in native conscious experience but that the native landscape is a powerfully visual idea. Whether it is resource extraction or water pollution, a critical means of entry to and arrival at a rich landscape of stories is the image. There is an important relation to the land that is akin to knowledge, and thereby, akin to power.

In the Chemehuevi, it is narrated:

The body of our creator, who was a woman, stretched her body and sent the animals to the edges of her body to tell her when she was big enough. Wrapped around the ocean, big enough.

To re/matriate the land, to steal back and transform such power, indigenous peoples are decolonizing the self-image—that is, the internal and personal self knowing. Recanting “we’re still here”, native people envision what ideas, chords, and memories to take into the future by ways of art and praxis, like Romero’s daughter in dance and the stories in her ferocity.